Indigo Women

Colonialism and the Sexualization of Textile Production in Sumba, Indonesia

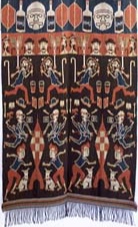

A young tourist has just arrived home with a woman's sarong seeped in deep blue, it smells pungent and slightly sweet, overwhelmingly raw, unprocessed, or moro. The smell directs her mind back to a dank little shack outside an ancestral village in the deep, velvety green mountains of West Sumba. The indigo fumes waft from the cracks in the wood structure as the dye ferments in the wet heat of the west side of the island. A vat of greenish liquid is being churned by an old woman, creating an island of frothy, vibrant blue scum on the rippling surface of the liquid. The woman’s hands are stained dark blue from hours of dipping and soaking threads in the indigo’s “dead, black blood,” called ruto mate. She wears a sarong around her hips that bleeds this deep, raw, ruto mate in languid stripes, the moro blue pooling into spiraling crab symbols that scuttle across the edges of the saturated fabric. The crab designs fluttering around her hips are a projection of her identity as a powerful woman, one with mysterious intelligence and a modern economic assertiveness.

Textile production has long been the sacred labor of women on the island of Sumba, a practice that is inextricable from the notions of witchcraft, reproductive medicine, female sexuality, and now female economic success. Though hand dyed and woven textiles still act as a prominent form of currency in Sumba, the introduction of a global tourist economy and modern conceptions of money over the last four decades have challenged the traditional values of its culture and the art that it produces. The women weaving this transcendent cloth work are called tou morongo, or “people who handle blue substances,” and through their threads they negotiate the boundaries between local and global, ritual and commercial, traditional and modern, taboo and temptation. This new female acquisition of wealth has effectively disrupted gendered roles in commercial activity on the island, which when understood by Sumbanese society using the preexisting image of the yora “spirit mistress” as a framework, has solidified this feminist folklore as an icon of female determination and success. With the combined threat of financially independent women and the codependent tourist market, new fears and resentments have arisen among village communities, but the door has been opened to a new era of female financial assertiveness. Janet Hoskins deliberates that “art and commerce are supposed to be separated, but are in fact nearly always inextricably linked,” a fact that can be seen in Sumba’s indigo-seeped, intricately woven response to the modern capitalist expansion that is the global tourist market. The indigo artists of Sumba have not only gracefully retained the traditional methods of textile production on the island, but proven that this raw, bleeding moro quality is inextricable from its success in the modern global art market.

Although western style clothing is readily available even in the most remote rural markets, all Sumbanese women and girls still learn how to weave and tie threads. The process of preparing the indigo is a fundamental aspect of the “blue medicines,” or “blue arts” which are referred to using the term moro as well, and include herbalism, midwifery, witchcraft, and abortion. Hoskins suggests that female herbalists and midwives have developed theories of reproduction around the metaphoric similarities with the process of fermentation in indigo preparation partly due to the fact that “certain roots and barks are used both to control the bleeding of color in textiles and to control the bleeding of women’s bodies.” These substances are strictly handled by older women who have gone through menopause as it is believed the mere sight of the ruto mate could cause reproductive harm or miscarriage if pregnant.

The symbolic relationship of dye fermentation with reproduction transforms the work of the tou morongo from a material practice to a spiritual practice, a meditation on materiality and the semiotic messages that it translates. By reading the iconography woven into the social skins (or “super skins” as termed by Catherine Allerton) that are Sumbanese textiles, we can see the way tou morongo women adapt to the changes that the modern global tourist economy brings to the island.

The images woven into these fabrics traditionally represent bridewealth items as well as embodying some of the secrets the artist would have learned from her elder practitioners of the “blue arts.” The crab icon appears often among the textiles made by and for these revolutionary women as a symbolic representation of their invaluable female intelligence, sexual power, and flourishing economic prowess. These traits, as perceived by Sumbanese society, may imply a sense of dishonesty or treachery associated with the obsession with wealth, but they have also solidified the new association of women with bookkeeping and money management skills. As women have honed in on their crab-like talents of calculation and craftiness they have translated historic changes through adapting foreign iconography like these images of knights, lions, and crests inspired by coins brought to the island by Dutch missionaries.

The image of a powerful Sumbanese woman, harnessing her sexual powers and supreme cleverness to produce a form of wealth that is free of social obligation has existed in the form of a “wild spirit mistress” or “demonic patroness,” called a yora, since before modern concepts of money were introduced to the island. Sumbanese society has come to understand this new wave of mysterious female entrepreneurs through the framework of the preexisting yora icon, who is said to meet noblemen in secret, sometimes taking the form of a crab, snake, or bird while in the nobleman’s bed. The implications of the means of wealth accumulation in Sumba are strong; wealth accumulated by social means holds a certain value and truthfulness through intimate exchange that antisocial, government supplied or mysteriously untraceable wealth lacks. Webb Keane argues that the yora, as well as newer concepts of market, money, and government development projects are “distinguished by the inexplicable entry of money from no comprehensible or stable source,” and therefore, the threat of loss. So, as women began to support themselves by means of the commercial market as well as government jobs like teaching, where the money has no local ties from the exchange of goods, the yora grew to be the Sumbanese people’s mode of rationalizing this new seemingly source-less female wealth. This lack of truthfulness of honorability is associated with the matrilineal hereditary witchcraft that is believed by Sumbanese people to be a product of resentment harbored from times of slavery, thus the lowest classes, people whose ancestors were slaves, are the ones who are able to exercise their cunning and skill with money without the restraint of socially enforced honor. The seemingly “antisocial” acquisition of bank loans and tourist capital that women have recently harnessed through textile entrepreneurship fits perfectly into Sumba’s preexisting understanding of yoras, creating a new icon of modern female-controlled tourist wealth.

Local production of textiles in rural Sumba has never been higher; tourist dollars flow into the hands of Indigo Queens as the island continues to be fetishized for the icons of its ambivalent resistance to modernity. The fear has been that the introduction of modern dyes and commercial means of producing textiles at high speeds will eradicate their symbolic significance, rendering them inadequate for local ritual use. However, women weaving at the forefront of this expanding Sumbanese commercial textile market have made a sincere effort to reinterpret old cloths and traditional designs in a way that preserves integrity while still maintaining success in the global tourist economy. These female entrepreneurs have embraced their profession's local occult implications along with its modern economic opportunities in the global market, effectively transcending both traditional indigenous and colonial conceptions of the role of women in Sumbanese society.

Works Cited

Adams, Marie Jeanne. System and Meaning in East Sumba Textile Design: a Study in Traditional Indonesian Art. University Microfilms International, 1980.

Allerton, Catherine. “The Secret Life of Sarongs.” Journal of Material Culture, vol. 12, no. 1, 2007, pp. 22–46., doi:10.1177/1359183507074560.

Hoskins, Janet. “The Menstrual Hut and the Witch's Lair in Two Eastern Indonesian Societies.” Ethnology, vol. 41, no. 4, 2002, p. 317., doi:10.2307/4153011.

Hoskins, Janet. “In the Realm of the Indigo Queen: Dyeing, Exchange Magic, and the Elusive Tourist Dollar on Sumba.” What's the Use of Art? Asian Visual and Material Culture in Context, by Jan Mrázek and Morgan Pitelka, University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2008, pp. 101–126.

Keane, Webb. “Money Is No Object: Materiality, Desire, and Modernity in an Indonesian Society.” The Empire of Things: Regimes of Value and Material Culture, by Fred R. Myers, School of American Research Press, 2008.

Morrell, Elizabeth. Securing a Place: Small-Scale Artisans in Modern Indonesia. Southeast Asia Program, Cornell University, 2004.